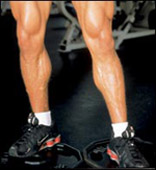

Muscular Legs

Five Exercises to Add Meat to Your Legs and Definition to Your Calves

by Dr. Clay Hyght

When people speak of training legs, it seems that the quadriceps muscles garner all of the attention. Hamstrings and calves tend to be thrown in at the end of a leg workout, almost as an afterthought. Iím here to tell you, doing three sets of lying leg curls and three sets of calf raises will not provide adequate stimulation to your hams and calves. To avoid half-heartedly training these muscles, I recommend you train them by themselves or, at least, before training quads.

Unless you plan on wearing pants every day for the rest of your life, your goal (visually speaking), should be to own a pair of hamstrings that have some sweep to them when youíre viewed from the side. As for calves, shoot for a nice flair that can be seen from both the front and the rear, and some depth that can be seen from the rear and the side. As for sports performance, strong yet flexible hamstrings are of utmost importance in any sport that requires running. Calves would rank a close second in running sports but would earn the number one spot (tied with glutes) in sports that require jumping like basketball or volleyball.

Without further delay, letís go over a simple yet proven routine for building strong, sweeping hamstrings and powerful, diamond-shaped calves.

Lying Leg Curls

Because the hamstring muscles (well, three of the four) cross both the knee and the hip joints, itís important to pay attention to the movement across both joints. When most people do lying leg curls, they allow their lower backs to arch, rotating the pelvis forward. This lengthens the hamstrings across the hip joint while it is simultaneously being shortened across the knee joint. Since the goal of the leg curl is peak, or maximum contraction of the hamstring muscle, try to avoid rotating your pelvis forward and arching your back when you curl the weight up.

Starting position: It helps to begin by supporting your upper body on your elbows instead of lying all the way down. Then, before you begin to curl the weight up, tighten your glutes and abdominal muscles, rotating the pelvis backward and flattening out the curve in your lower back.

The exercise: Maintain this spinal and pelvic position while curling the weight up as high as you can. Youíll immediately notice that you have to use a really light weight and that you can only curl the weight a little more than halfway up to your glutes. Thatís the way itís supposed to be. You will also notice, if you do this variation correctly, that you get a much stronger contraction in your hamstrings than doing them the traditional way. Thatís because youíre contracting the muscle across both ends as opposed to contracting it across one end and relaxing it across the other end.

Donít worry. It takes most people a few workouts to really get the hang of this. Have a partner watch your form to make sure you keep your back flat and pelvis in place. As with most exercises, curl the weight up in about one second, then slowly lower it, taking three to four seconds to return to the starting position.

Perform four sets of 10 to 15 repetitions each.

Tip: If you can curl the pad up until it touches your butt or top of your hamstrings, youíre not doing it right.

Bench Push-Offs

Hereís an exercise you wonít see too often. Thatís too bad because bench push-offs are a great way to hit the hamstrings as well as give a little extra stimulation to the coveted gluteus maximus muscle.

Starting position: Lie flat on your back with your body perpendicular to a flat bench. Position yourself so when you place your feet on the top of the bench, your knees are bent almost 90-degrees. Rest your arms along your sides on the ground for stability.

The exercise: To begin the movement, push off the bench with your right leg, lifting your lower body off the ground and your left leg off the bench. After pushing yourself up as high as you can, pause for a second and then slowly lower yourself to the point just before the base of your spine touches the ground. Then repeat for the desired number of reps with that leg before switching to your left leg. Your tempo should be one to two seconds up, a one second pause at the top in the contracted position, then lower yourself in three to four seconds.

Perform three sets of as many reps as possible.

Dumbbell Stiff-Llegged Deadlifts

In my opinion, the stiff-legged deadlift is the premier hamstring exercise. Many trainees forgo these, opting for another variation of the leg curl for one simple reason: stiff-legged deadlifts are hard. Any exercise that taxes as many muscles as the stiff-legged deadlift is going to be hard. Although the hamstrings will suffer the brunt of the load, not one muscle on the whole back of your body will go unstimulated after doing a set of stiff-legged deadlifts.

Starting position: Grab a set of dumbbells and hold them in front of your thighs. With a slight bend in each knee, your back arched, lean forward about 15 degrees by bending at the waist. Now youíre ready to begin.

The exercise: Start the movement by bending forward at the waist, with the dumbbells traveling in front of your legs toward your feet. Go down until you feel a nice but comfortable stretch in your hamstrings. (For most people this will put the dumbbells just below knee level in the finished position. If youíre going much lower than that, youíre most likely flexing your lumbar spine or rounding your lower back.) Slowly reverse the motion by contracting your hamstrings to bring you back to the starting position.

This movement should be done in a slow manner up and downóabout three to four seconds in each direction.

After a light warm-up set, perform two sets of eight to 12 repetitions.

Tip: Make sure to keep a slight bend in your knees throughout the entire movement to avoid hyper-extending your knees.

Tip: To avoid a lumbar disc herniation, maintain an arch in your lower spine throughout the entire movement.

Unilateral Dumbbell Calf Raises

Now weíre going to hit the diamond or ball-looking muscle of the calf complexóthe gastrocnemius. To do so lets perform calf raises using body weight and a dumbbell for added resistance. To make sure both calves get equal attention, do these unilaterally (one side at a time). If one side happens to be stronger than the other, perform the weaker side first followed by the same number of reps with the stronger side. Over time, this should correct any strength deficit.

Starting position: To begin by training the left calf (which is often weaker than the right), grasp a dumbbell with your right hand while using your left hand to grasp a solid object for balance. Place the ball of your working foot on the edge of a steady object thatís high enough off the ground to allow you to drop your heel as low as you can without it touching the ground.

The exercise: From the bottom stretched position, begin the exercise by maximally contracting your gastrocnemius to raise your heel as high as pssible. After pausing for a second, take about four seconds to lower yourself back to the staring position at the bottom of the movement. Avoid resting at the bottom before beginning the next repetition.

Perform four sets of 10 to 15 reps.

Seated Calf Raises

To finish training the calf complex, we need to hit the deep calf muscle called the soleus. To do so, the knee should be flexed (bent) to an angle of about 90 degrees. For that reason Iíve selected a fairly traditional exercise thatís hard to beatóthe seated calf raise.

Starting position: Begin with your heels in the bottom position of your ankleís range of motion with the pad of the machine resting comfortably across your thighs a few inches above your knees.

The exercise: Slowly press the weight up as high as possible while simultaneously undoing the safety latch. After pausing at the top in the contracted position for one second, slowly lower the weight back to the starting position. Your tempo should be about three seconds up and down, separated by a one-second pause in the top position.

Perform four sets of 15 to 30 reps each.

Caution: Make sure to have a spotter handy in case you get stuck in the bottom position, too low to engage the safety catch.